38. You are an ancient artisan

How to make it work in the new economy

Part of why I write TMMW is to look at how absurd the status quo is. I take the flashlight out of the drawer, click it on, and point it at one of the weirder parts of the way we live.

"Look at that over there! That dude is an influencer. Isn't that wild?"

The deeper reason is that I want this to be a space that supports people living creatively, to be independent, to thrive, and to be in touch with what inspires them.

I do this to objectify things that may otherwise be accepted as "normal." The point of naming these things is to gain the ability to separate from them, to become more free.

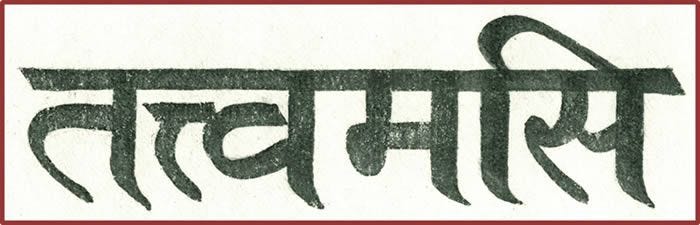

On my arm, I have tattooed tat tvam asi, Sanskrit that can translate to "thou art that." It's from the Upanishads.

The true meaning of the term is, for me, the subject of awe. It's not reducible. Still, I believe there are practical ways to apply profound truths and one way to apply "thou art that" is through the effort of bringing discernment. Discernment is necessary to see things as they are.

Discernment stems from the self in the effort to align with self-knowing. The very fact of your consciousness proves that a part of you is already in touch with this nondual and transformed state.

Ancient digestion

I've never been one for fad diets (or diets at all), but I remember when I first started working out, I struggled to be able to put on muscle mass. I simply couldn't eat enough to make this happen. A friend of mine had the opposite problem. While I was shoving my face with anything and everything, he was experimenting with "the caveman diet." This caveman diet came well before the emergence of the paleo diet. This diet was framed in the context of "carb cycling" -- some days you eat carbs, some days you eat no carbs.

My weightlifting buddy, who is now a lauded AI researcher, explained about the caveman diet that our digestive systems haven't fundamentally changed over the course of a few generations. We have the same basic bodies as our human ancestors, back to "the caveman days," so theoretically, we should be eating the way our human ancestors did.

The idea appealed to me more than the diet. Many traditional practices, particularly those related to food and diet, are regaining popularity as potential solutions to modern health issues. For example, there's renewed interest in naturally fermented foods, which have been consumed for centuries. This trend reflects a broader curiosity about historical approaches and their potential to solve problems that come up as we live on the cutting edge.

Just as our digestive systems haven't fundamentally changed from how they were when we were living in caves, clubbing things and pulling each other around by the hair, I think the same is true for our psyches.

The economy of Steve and Joe

Because of this, it may be fair to say that modern knowledge workers (a fancy way of saying people with desk jobs) try to unconsciously situate themselves into a peasant laborer framework. Think of it like this. Old Economy Steve went to work for Joe Corporation and was thereby able to support his family and live a life he found enjoyable, although not necessarily fulfilling.

Joe Corporation in this example is the wealthy landowner. He owns the land and provides for Steve's community needs and basic safety. In return, Steve and his family toil away so that Joe can remain fat and sassy.

Believe me when I say that I’m not judging either of these. I can personally relate to the desire for peasant stability and the desire for power exemplified by the wealthy landowner of yore.

The thing is, this model is becoming less stable. Joe Corporation has discovered witchcraft and machinery, and things have gotten weird for him. As a result, Steve can't really count on Joe for any real security.

The times have changed, but our internal disposition toward these models remains. Instead of Viking raids, there are mergers and mass layoffs. The psychological templates for these two roles aren't as reliable as they once were. Our desire for safety and stability as peasants, for example, is no longer very achievable. There’s value in making the shift towards our inner artisan.

New model for artisans

Side gigs are now basically the norm. Think of your circle of friends and family. How many among them either have something that they also do on the side or want to?

It's becoming rarer to find Old Economy Steves anymore, the person who sets out on the modern version of a career path which equates psychologically to the successful peasant laborer. Does that mean we have a market flooded with artisans?

In other words, is there more competition in having your own creative enterprise? I don't think so. We all still have the same basic wiring. Deep down, we still wish for something stable to hang our hats on. It's hard to overcome that in the quest for self-knowing, authenticity, and truth. That's why many side gigs are more or less get-rich-quick schemes. We’re yearning for a return to the honest peasant life. It's hard as hell to abide in a place that is not supported by a system.

Many people dream of starting a business. A restaurant, say, or a creative life as a writer. Such a business is centered around creating something that you get paid for. The fabric of society in most places supports such a thing in theory but seldom in truth. Charting your path--and making it work long-term--can be bloody difficult. Psychologically, just as difficult as a person who grew up as a peasant laborer deciding to be an artisan. To leave the farm with their goat and set up shop in a neighboring village.

Societal dogma says, "Wouldn't it be nice if we could all do that." The artisan says, "But you can if you want to! You can! And I wish you would." It's unthinkable that such dreams are in any way regarded as selfish because, fundamentally, a person is saying, "I want to earn my living by working at something creative that I love."

This is why it's important to put our money where our mouth is, to support the creator economy -- to buy handmade goods, to support independent arts, and to above all, embrace these things ourselves.

Just as it's true that we're still cavemen inside, we're still basically the same as we were during other epochs of human history. We also have a deep inner knowing of how it feels to be a peasant farmer or an artisan.

Humans spent thousands of years in which most were hunter-gatherers and peasant farmers. In my time in Tuscany, I learned of the mezzadria system - a sharecropper system that lasted successfully for a very long time. Under this system, workers kept half of what they grew, and they gave half to the count, the wealthy landowner.

Songs during seasonal festivals hosted by the count celebrated this system, where despite it being half and half, the farmer would, of course, choose to win one over on the count by keeping the best half for themselves. It's something both lovable and problematic of human nature: the desire to keep the best half for oneself.

I believe that the creative life strives to leave it all on the playing field. The artisan’s life is the opportunity to live fully. Sometimes, you get the good half, and sometimes, you don’t. But that’s not what it’s about. It’s about how it feels to do the work.