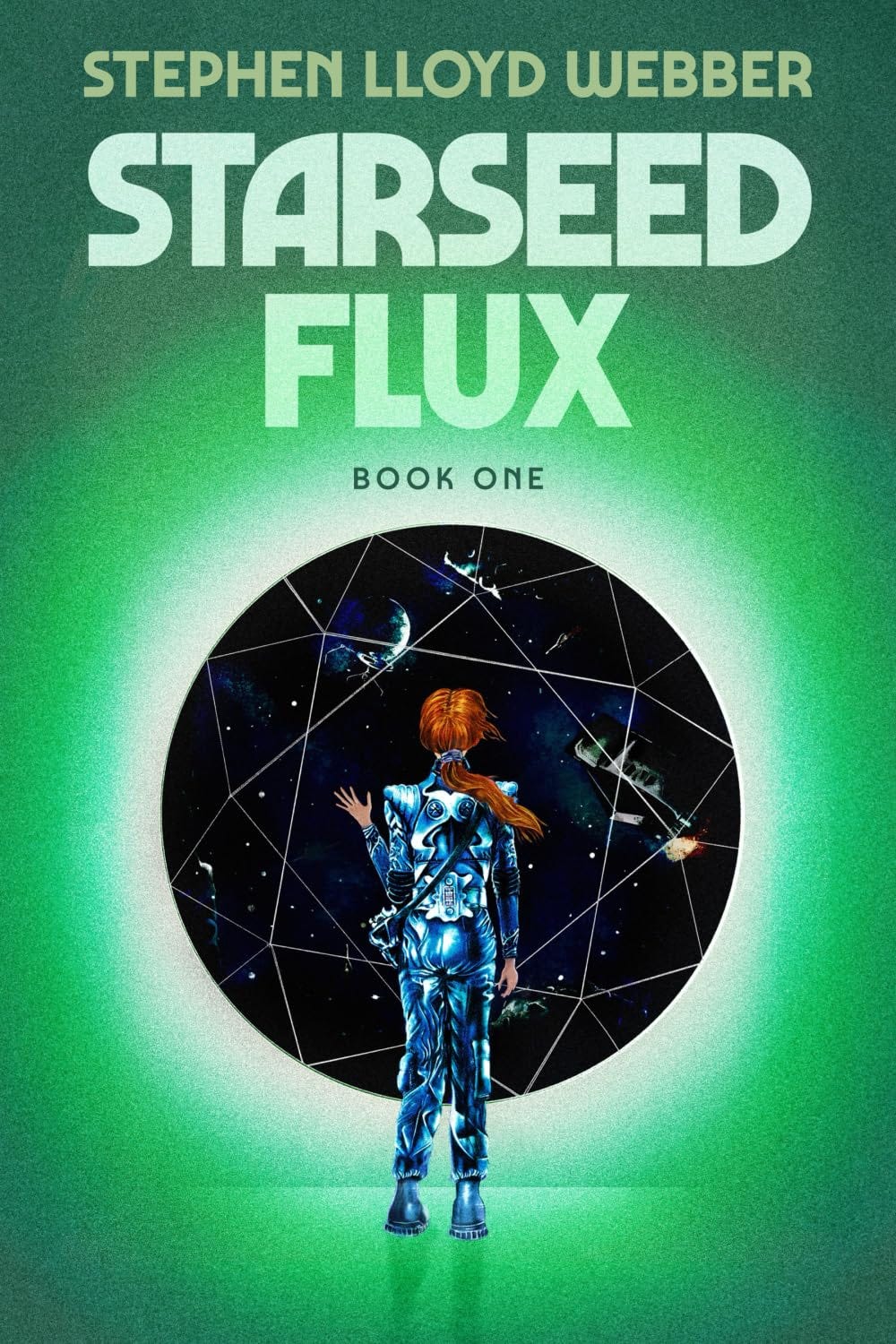

The scaffold method (and my first YA scifi novel)

Starseed Flux is out now

As a kid, there are movies you watch once. And there are movies you rewatch until you know each scene by heart.

For me, growing up, the rotation was: Batman (Keaton-era), Indiana Jones, Star Wars. And then, every so often, slipped in between the epics: Adventures in Babysitting.

I don’t know where that one came from, but it stuck with me. Elisabeth Shue gets roped into driving some kids into Chicago to rescue her friend, and everything goes wrong. A blues club. A car thief with a heart of gold. A knife fight. The kids almost die several times, but she gets them home, and nobody tells the parents.

A different kind of experiment

Starseed Flux is my first YA sci fi. It started as an experiment in structure.

I’d been kicking around a science fiction premise for a while: suppose there was a grand initiative to travel to the next solar system but faster-than-light travel doesn’t exist. Even if the ship goes really fast, it would still take more than one human lifespan. Extrapolate this further and you could imagine a grand endeavor to travel to distant solar systems. Getting anywhere would mean the coming and going of multiple generations of human beings. The mission would feel very different to the person forty generations in than it might have to the one who bravely signed up for it. What would life be like on a multi-generational mission bearing the weight of a purpose you never chose?

I had characters. I had the broader universe. What I didn’t have was a narrative spine.

Then I remembered Adventures in Babysitting, and I went to work. I took the film’s synopsis and expanded it into a scene-by-scene breakdown. Then I performed a kind of find-and-replace operation: my characters, my world, my story, but running on the existing chassis.

I wasn’t trying to write a science fiction adaptation of that movie or really be concerned with anything besides my embodied memory of its story beats. I just used it as scaffolding. Really, the exercise could work with any story that has a good underlying structure. I wanted to start with something fun.

The dual memory

Writing this way was interesting, because during the planning process I was holding two stories in mind at once. This is what was happening in the movie at this point. This is what’s happening in my story.

At first, the parallels were close. By the end, there are stretches where nothing lines up at all, and the two worlds are very different. The characters are completely different. The exercise shows the story take on a completely different life, not dictated by its structure.

The choice to work this way kept me from overcomplicating things. When I start building a world, I inevitably generate more characters, more backstory, more threads. The temptation is always to let the story sprawl. Having the scaffold meant I could say no, this scene serves this function, that character appears here for this reason. And move on.

The story

Mott Fortress was a maintenance worker on the IHC-111, one of three multi-generation ships carrying what remains of humanity on a centuries-long mission to seed life across the cosmos.

She’d never questioned the mission. Why would she? She was born into it. Her job was to keep systems running, follow protocols, and eventually pass the work to her own clone. She understood life as something measured in centuries-old routines.

Then everything went wrong. It started small. She was asked to supervise two junior clones from one of the royal families while their elders attended important meetings. Annoying, but manageable. Then her best friend Beryl called, frantic, claiming she’d witnessed a ghost ship, vast and cloaked, shadowing their fleet, and that she was now trapped in a medical facility.

What followed was an unauthorized rescue mission that spirals out of control. It’s something of a coming-of-age story. Mott spends the book becoming the kind of person who can hold responsibility. Which means failing spectacularly over and over again.

The title comes from the physics (flux referring to some sort of amazing starship drive technology) but also from the condition of living in permanent transition. The seeders exist between origin and destination. They’re not the people who left Earth, and they’ll never be the people who arrive. They’re the ones who keep the lights on.

What does it mean to live a life that exists purely in service of a future you’ll never see?

An excerpt

Here’s a passage from early in the book. Mott has just been stood up by her boyfriend and is counting stars on the observation deck:

My eyes fixed out beyond the transparent pane on the void of space. I was counting the stars—or trying to, anyway. It’s a game that my boyfriend Tam and I have: keep your eyes fixed straight ahead and try to count the total number of stars in your field of vision. The game had started on one of our first dates, when I’d confessed that my sensitivity to picking up other people’s emotions sometimes made it hard for me to know what I was feeling myself, and in those moments I needed to decompress by staring out at space. He seemed touched by me mentioning this, and suggested we head here, to the observation deck, to see how fully we could decompress in each other’s presence. And before long, it became our simple, secret way of enjoying the warmth of each other’s presence against the backdrop of outer space’s far reaches.

It was an impossible game. There are far too many stars and nebula to count, but I loved to try, to just stand and take it all in, make my field of vision as broad as it could be and estimate the tens of thousands. Or rather, try to stretch the sharp clarity at the center of my vision so that it expanded wide enough to take in every distinct star, the shape and size and color and the unconstellated proportions between each and every dot against the rich pure black of space.

What’s next

I have a detailed plan for book two. The story continues, the stakes expand, and some of what got set up here pays off in ways I’m excited about.

But for now: book one is here. You can read it. I hope you will, and I hope you enjoy it.