'Morning Pages' Doesn’t Go Far Enough

Musicians have scales. Athletes have drills. What do writers have?

What practice do writers have? We have freewriting.

Many people are familiar with freewriting in the context of “morning pages,” Julia Cameron’s well-known ritual of scribbling three pages longhand each morning before the critical mind clicks on.

To write morning pages, you wake up, grab a notebook and pen, and before you check your phone or make coffee, smoke your pack of cigarettes or whatever else floats your boat, you write three pages of whatever comes to mind. Stream of consciousness. You don't stop to think, you don't cross anything out, you don't reread. If you run dry, you write "I don't know what to write" or something until something else surfaces. The pages aren't for anyone—not even for you to revisit later. You just fill them and move on.

Morning pages are good. It’s a simple practice. Morning pages are the default recommendation for anyone who wants to loosen up their writing.

But I worry we’re dilly-dallying. The rise of AI and its widespread use as a replacement for the rigors and rewards of a regular writing discipline are going to have long-lasting ill effects on attention spans and creativity. We need to value the dreck and slog and bunk of the creative process a hell of a lot more.

AI can give you output. What about the process?

The brief history of getting unstuck

Freewriting has been around longer than Cameron’s morning pages. Peter Elbow was writing about it in the 1970s, teaching generations of students to keep the pen moving without stopping, to separate the act of creating from the act of critiquing. Before him, the Beats were already on the case, and Kerouac famously taped sheets of paper together into a continuous scroll so he could type On the Road without the interruption of feeding new pages into the typewriter. He didn’t want anything to break the flow.

The lineage goes back further still. There was stream of consciousness as a literary technique, experiments with automatic writing, and surrealists pulling imagery from dreams. What all these share in common: the value of getting out of your own way.

Cameron’s morning pages simplified all of this into something anyone could do. Three pages, longhand, first thing in the morning. Don’t think, just write. It’s entry-level freewriting with a comforting ritual structure, and it’s helped lots of people develop a regular writing habit.

But for many writers, morning pages has become the whole workout instead of the warm-up. They lower their defenses while they do the morning pages and then shift gears into work mode. We need to bring what’s ‘free’ about a morning freewrite into the other writing that gets done.

Be like Frank

It's 1959 and Frank O'Hara is on his lunch break from the Museum of Modern Art. He walks out onto 53rd Street with a small notebook or maybe just a scrap of paper. He buys a cheeseburger. He watches the construction workers eating their sandwiches on the girders. A blonde woman walks by. He notes the glass of papaya juice, the Puerto Ricans on the avenue, a sign for a bullfight poster. He's writing while he walks, or he's writing later from memory, or both—the distinction doesn't matter because for O'Hara the noticing and the writing are continuous. What results is “A Step Away from Them”:

A Step Away from Them

By Frank O’Hara

It’s my lunch hour, so I go

for a walk among the hum-colored

cabs. First, down the sidewalk

where laborers feed their dirty

glistening torsos sandwiches

and Coca-Cola, with yellow helmets

on. They protect them from falling

bricks, I guess. Then onto the

avenue where skirts are flipping

above heels and blow up over

grates. The sun is hot, but the

cabs stir up the air. I look

at bargains in wristwatches. There

are cats playing in sawdust.

On

to Times Square, where the sign

blows smoke over my head, and higher

the waterfall pours lightly. A

Negro stands in a doorway with a

toothpick, languorously agitating.

A blonde chorus girl clicks: he

smiles and rubs his chin. Everything

suddenly honks: it is 12:40 of

a Thursday.

Neon in daylight is a

great pleasure, as Edwin Denby would

write, as are light bulbs in daylight.

I stop for a cheeseburger at JULIET’S

CORNER. Giulietta Masina, wife of

Federico Fellini, è bell’ attrice.

And chocolate malted. A lady in

foxes on such a day puts her poodle

in a cab.

There are several Puerto

Ricans on the avenue today, which

makes it beautiful and warm. First

Bunny died, then John Latouche,

then Jackson Pollock. But is the

earth as full as life was full, of them?

And one has eaten and one walks,

past the magazines with nudes

and the posters for BULLFIGHT and

the Manhattan Storage Warehouse,

which they’ll soon tear down. I

used to think they had the Armory

Show there.

A glass of papaya juice

and back to work. My heart is in my

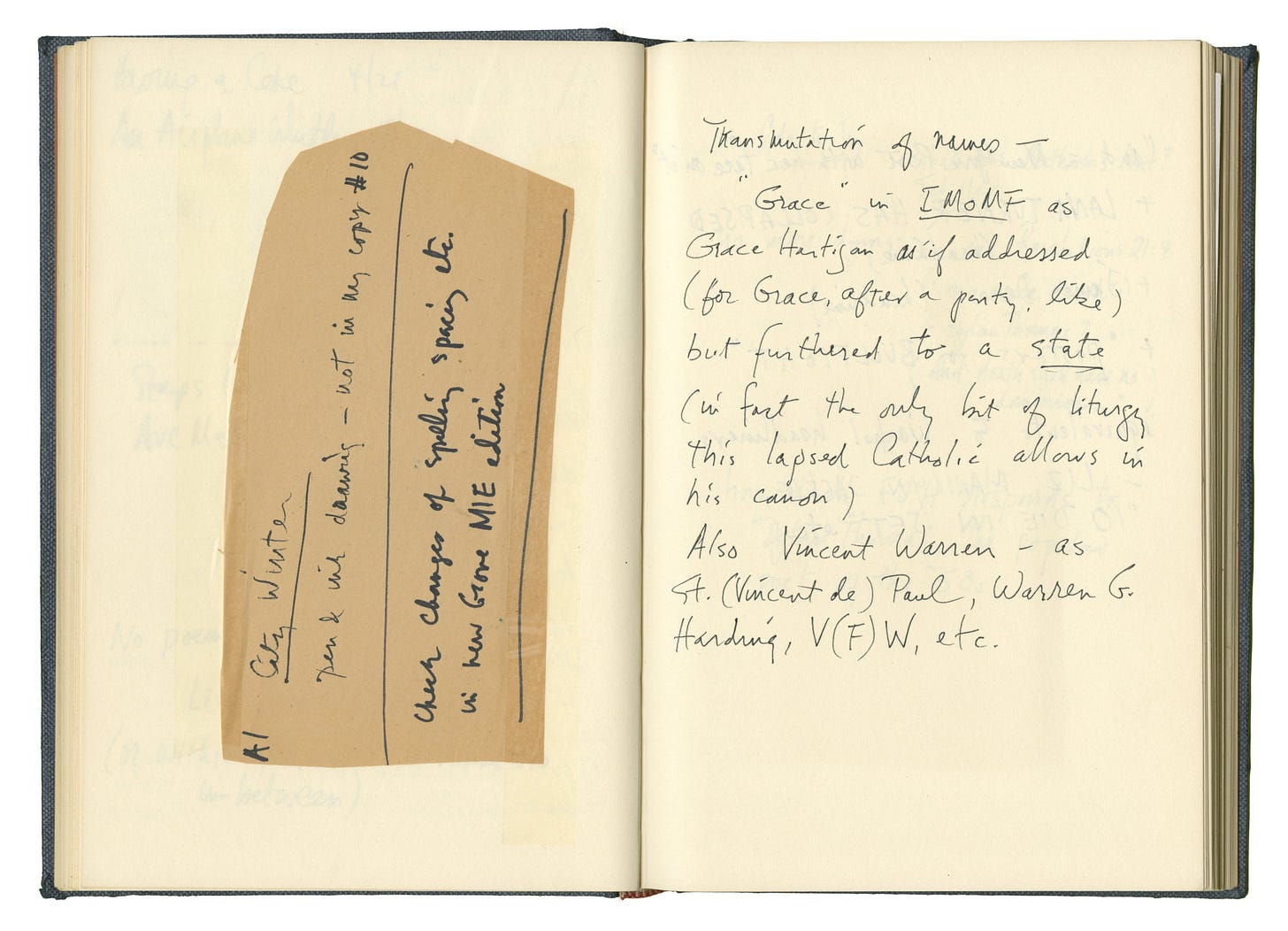

pocket, it is Poems by Pierre Reverdy.O'Hara sometimes gave poems away. He left them in drawers, didn't bother to publish. The point wasn't the artifact. It was to stay in contact with his own perceiving mind, to keep the channel open between what he saw and what he could say about it.

Nobody could have written those poems for him. The poems are inseparable from the act of perception that made them. If O'Hara had outsourced the words, there would be nothing left—not just no poem, but no walk, no lunch hour, no life pressing against language. AI can give you sentences about a man walking through midtown. What it cannot give you is the only thing that matters: being the one who walks, and sees, and finds the words yourself.

The content problem

Writing is too often strangled by expectations around content. People approach the blank page believing they need to have something to say before they can say it, when in fact the opposite is true. Morning pages gives you permission to write nothing in particular. Just dump it out. Clear your head. Move on.

And now with AI able to produce passable content on command, there’s less of a need to adopt a writing discipline that will, over time, sharpen a writer’s voice and build skill. AI’s ability to produce writing puts all the emphasis on the output, on the product, on what it says. The assumption is that if the machine can produce the words, why bother with all that messy human process at articulation and feeling things out?

Social media amplifies this belief. The attention economy trains us to believe we need to constantly remind people of our message and brand just to exist. Post or perish.

But... the travails of writing are valuable as an exercise between brain and hand. Writing’s versatility is its value multiplier. You can use the same medium for digesting what surfaced in dreams, for processing and externalizing your personal aspirations, or just thinking on the page, exploring the seeds of poems or stories, playing with figurative language—similes, metaphors, the whole kaboodle. Writing gives everyone—not just authors—a way of symbolically representing what you feel and experience and observe.

Such personal writing matters whether or not anyone else ever reads it, and it has carryover effects to whatever “official” writing you eventually do—the writing where content matters, where you’re creating something for someone else, giving them an experience or information or entertainment. The private practice feeds the public work.

What happens when people drop the private practice because AI seems to provide whatever content they would want? A good friend of mine, actually, is in this situation.

He wants to write a book. He does still keep a regular journal. But he uses AI so compulsively, it’s had the unintended consequence of dissuading him from actually wanting to bring a book of his own authorship to the finish line. When he first discovered AI, it wowed him for how it would be able to streamline his writing workflow. And yet, he’s not coming any closer to completion with his book.

If he were my writing client, things would play out differently. The world would be a better place if there was a book with his name on its spine.

One place to start: asking more of the journal he already keeps.

Keep a writer’s notebook

Morning pages helps clear the mind, to get rid of the mental clutter so you can move on with your day. Which is great, as far as it goes. But all this AI hooha gets me more concerned about what “moving on with your day” entails. We need to get more serious about feeding our creative practice.

One practice everyone should do: keep a writer’s notebook—a portable, ongoing collection of raw material for your writing. Unlike a diary (which records your life) or morning pages (which clears your head), a writer’s notebook is inwardly informed but outward-facing. You’re hunting and gathering.

This should be playful. The poet Kenneth Koch used to have his students write poems “in the voice of” various things—a comb, the moon, a color. A writer’s notebook isn’t something you can get right or wrong unless you aren’t doing it.

It’s a writing practice that creates artifacts and seeds, useful fragments that might grow into something. You could use it to pull descriptions, quotes, or ideas captured on the fly into some other thing you’re working on. Or, you can just see it as a kind of regular drill or exercise.

What the practice can hold

Think about what a robust writing practice can actually contain:

The immediate stuff: processing dreams while they’re still vivid, noting what’s on your mind before the day’s machinery kicks in.

The generative stuff: experimenting with a metaphor, with the sounds of words and phrases, repeatedly and imperfectly trying to describe something you observed yesterday, playing with the rhythm of a sentence until it surprises you.

The practical: thinking through a problem, sketching out an idea that’s been forming, jotting down a phrase that might become a poem or essay or scene.

The somatic: describing bodily sensations, the goings-on amidst your intuitive weather, what you hear in the room, feeling the textures of language in your immediate experience.

All of this is more than head-clearing, and if you do it right, it spills into your day. It’s the writer’s equivalent of scales and drills. Deliberate regular engagement with the fundamental elements of the craft.

Process in an age of output

We miss the boat when we forget to value the process. Let’s suppose AI is great at output. Well, output still matters less than process. I want to live my life, not just achieve some result but never really exist.

When I make pottery, I do it because I love it. When I write, I put myself into my work.

Morning pages gets a lot of people started. It gives permission to write without agenda or judgment. But it’s time to push further and expand what an unburdened practice can hold.

It can be as simple as keeping a writer’s notebook. The discipline leaves you lighter, but also richer with fragments, images, and seeds of things that might become something.

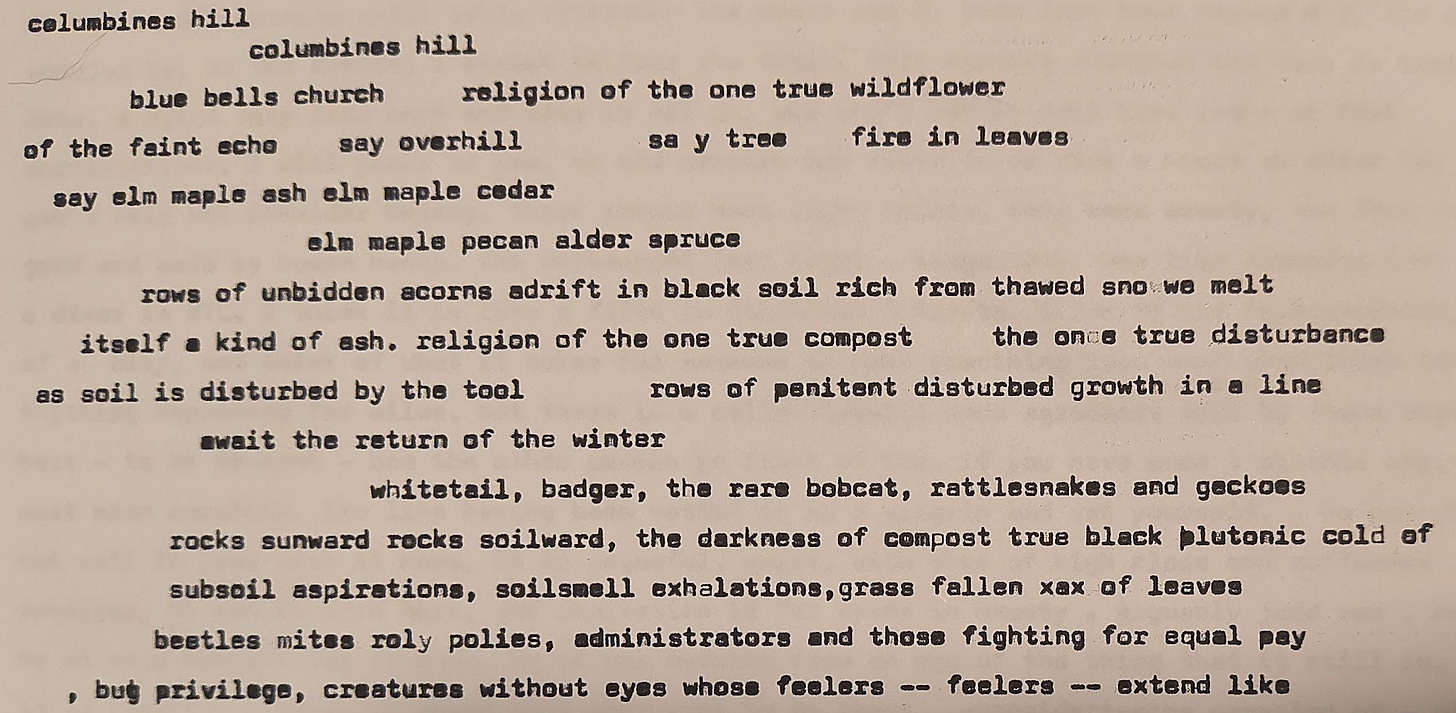

The Understory

Here are a few lines from the middle of a bit of writing on a very different topic. I was journaling, then hit a bit of a lull, and just started rolling around the sounds and impressions of words. It’s sort of an example of what I meant by “generative” in the above mention of what you can do with a writer’s notebook.

As always, if you have a work-in-progress or draft or excerpt that you would like to share, please do so. Simply hit reply/comment and paste it in.

Really interesting post. And inspiring. I will find one of Peter Elbow's books.

Here is an excerpt of one of my books (on my shelves) on writing and the creative process:

… So if you are to have the full benefit of the richness of the unconscious you must learn to write easily and smoothly when the unconscious is in the ascendant.

The best way to do this is to rise half an hour, or a full hour, earlier than you customarily rise. Just as soon as you can - and without talking, without reading the morning’s paper, without picking up the book you laid aside the night before - begin to write.

…

Becoming a Writer from Dorothea Brande, 1934, page 72